After two decades on the streets, I’ve developed a deep, almost poetic respect for the central line. This isn’t just a fancy IV, it’s the Cadillac of vascular access, the kind of gear that makes you whisper, “We’re not in peripheral land anymore, Toto.” Thanks to Kian Yorkton’s brilliant sketch (that hand-drawn gem you shared!), we’ve got a roadmap to dissect this beast, lumen by lumen, color by color, and placement by placement. So, grab a coffee (or a stiff drink, no judgment), and let’s unpack the anatomy of a central line with evidence, a dash of humor, and a nod to that diagram’s spot-on details.

What’s a Central Line, and Why Do We Worship It?

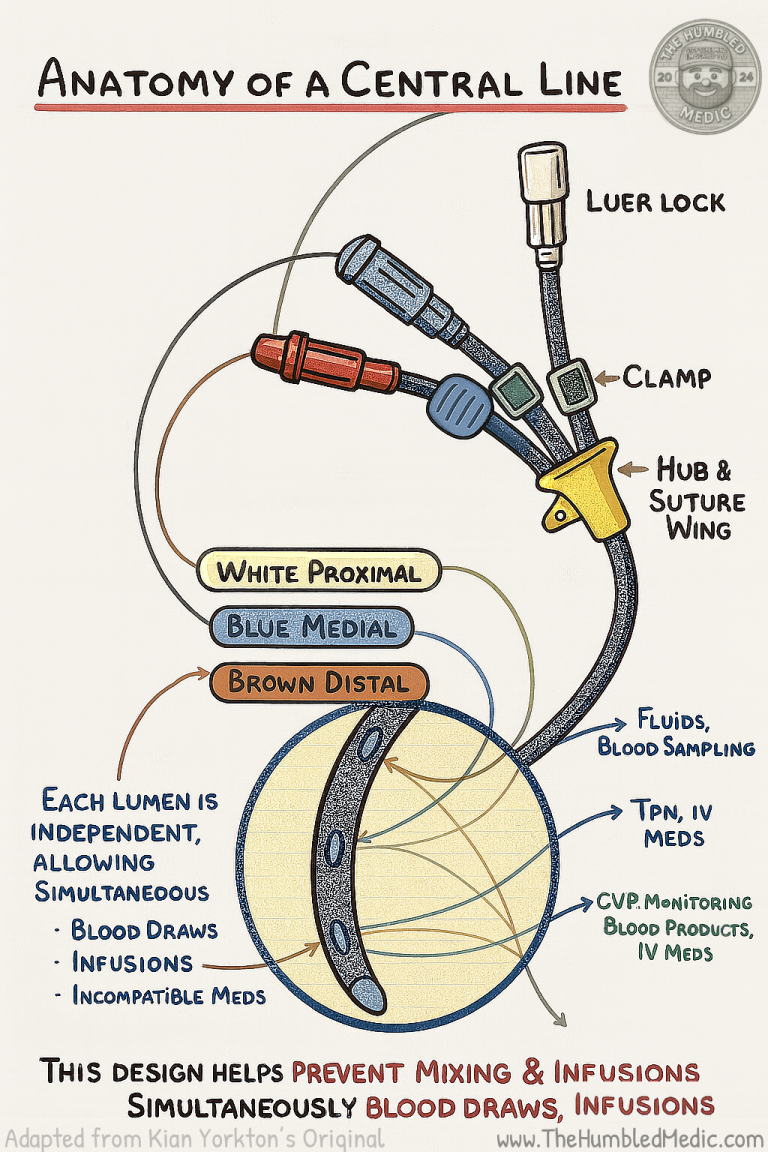

For the uninitiated, a central venous catheter (CVC) is a long, flexible tube parked in a big vein—usually the superior vena cava near the heart. Why? Because sometimes a peripheral IV is like bringing a butter knife to a gunfight. We’re talking septic shock, trauma, long-term antibiotics, chemo, or when your veins are hiding like they owe you money. Central lines deliver meds, fluids, and nutrition fast, and they let us monitor pressures like central venous pressure (CVP). The CDC’s 2021 guidelines (still gold in 2025) call them critical for ICU and emergencies but warn of risks like infection or thrombosis—so we don’t slap ‘em in willy-nilly. Kian’s diagram nails the core: “Each Lumen is Independent, Allowing Simultaneous: Blood Draws, Infusions, Incompatible Meds”—a multitasking marvel when you’re juggling Lasix and heparin in a crash.

The Lumens: Meet the Color-Coded Crew

Kian’s sketch shows a triple-lumen CVC with three ports, each tied to a tube inside the catheter. These lumens are color-coded (mostly) and have specific jobs, matching standard designs like those from Arrow or Bard. Let’s break ‘em down, blending the diagram with my field experience:

- White Proximal Lumen

- The Skin-Side Buddy: Closest to where the catheter exits the skin, this white port (labeled “White Proximal” in the sketch) is tagged for “TPN, IV Meds.” It’s typically an 18-gauge lumen, perfect for total parenteral nutrition or slow infusions like antibiotics when the other lumens are busy. I’ve used it for that one med I forgot to give earlier (we’ve all been there).

- Why White? It’s the “chill” color, a default for the proximal port in many kits. Kian’s diagram aligns with this, though I’ve seen purple or pink in some brands—always check the label, or you might end up with a TPN surprise in the wrong tube!

- Pro Tip: Stick to low-flow stuff here. A 2024 Journal of Vascular Access study warns against high-pressure infusions (like CT contrast) due to higher resistance at the proximal end, risking rupture.

- Blue Medial Lumen

- The Middle Child: Sitting mid-catheter, this blue port (labeled “Blue Medial”) handles “Fluids, Drugs, Blood Sampling,” per the sketch. It’s usually an 18-gauge lumen, the jack-of-all-trades for meds, fluids, or grabbing a blood gas. I’ve drawn labs from here during a bumpy transport—works like a charm.

- Why Blue? Blue’s cool and collected, standard for the medial port. The diagram’s multitasking role is spot-on, but the 2022 ASA guidelines remind us to avoid mixing incompatible drugs (e.g., Lasix and Versed) to prevent clogs.

- Pro Tip: Flush between meds. The independence Kian highlights lets you run incompatibles, but sloppy technique turns your catheter into a science experiment.

- Brown Distal Lumen

- The Heart’s Best Friend: At the catheter tip, closest to the superior vena cava, this brown port (implied by the diagram’s tip focus) is linked to “CVP Monitoring, Fluids, IV Meds, Blood Products.” As a 16-gauge powerhouse, it’s the go-to for high-flow needs like vasopressors or blood transfusions. A 2023 Critical Care Medicine study backs this, showing distal lumens reduce drug precipitation risks due to better flow.

- Why Brown? Bold and bossy, brown’s a common distal port color (though some kits use red). Kian’s tip placement aligns with evidence that it should sit at the cavoatrial junction.

- Pro Tip: Don’t hook TPN here if other lumens are in use—mixing drugs can turn it into a chemistry lesson gone wrong.

Color Coding: Why It’s a Love-Hate Thing

Kian’s diagram uses white, blue, and brown, which tracks with many triple-lumen kits, but color coding isn’t universal. The CDC and ASA stress clear labeling to avoid mix-ups—especially in the ED where I once saw a nurse bolus propofol into a TPN line. (True story. Nobody laughed.) Always trace the line from port to hub, and if in doubt, ask the doc who placed it—they love flexing their ultrasound skills.

The Hardware: Ports and Clamps

The sketch includes a “Luer Lock” (that twisty connector), a “Clamp” (to stop flows or prevent air embolism, trust me, you need it), and a “Hub + Suture Wing” (where it meets the skin and gets stitched). These are the CVC’s backbone, and Kian’s got ‘em nailed. The suture wing keeps it secure during that wild ambulance ride, clutch when you’re stabilizing a trauma patient.

Where and Why: The Great Placement Debate

The diagram doesn’t specify sites, but the context (CVP, TPN) points to common spots—internal jugular (IJ), subclavian, or femoral—backed by 2025 evidence:

- Internal Jugular (IJ) Vein (Neck)

- Why Here? A straight shot to the superior vena cava, with a 1-2% lower infection rate than subclavian (NEJM 2023 meta-analysis). Great for CVP monitoring and short-term use, like sepsis. I’ve placed IJ lines in the field with ultrasound—lifesavers.

- When? Emergencies or ICU stints. Patients hate the neck dressing, though, especially if they’ve got a Santa beard.

- Subclavian Vein (Chest)

- Why Here? Lower long-term infection risk (CDC 2021) for TPN, tucked under the clavicle. Comfy for patients, but a 1-2% pneumothorax risk (Chest 2024) keeps us cautious. I’ve seen a rookie doc collapse a lung—room got quiet fast.

- When? Long-term needs like chemo or dialysis.

- Femoral Vein (Groin)

- Why Here? Quick access in codes or trauma, easy with ultrasound. But a 5-10% infection rate (Critical Care 2023) makes it a last resort. I’ve placed femoral lines in a bouncing ambulance—not fun, but it works.

- When? Short-term, no other options.

Why We Care About Placement

Placement’s about safety and function. The catheter tip should hit the cavoatrial junction for optimal flow, per a 2024 Journal of Vascular Access review. Too high, and you risk thrombosis; too low, and arrhythmias loom. Post-insertion X-rays are a must—even us seasoned folks can’t eyeball it.

Incompatible Meds: The Wild Card

Kian’s sketch lists “Lasix + Versed,” “Heparin + Protamine,” and “Levophed + Sodium Bicarb”—classic incompatibles that can precipitate or neutralize. The independent lumens let us run these simultaneously, a game-changer. The 2022 ASA guidelines stress flushing between doses to avoid turning the catheter into a volcano.

Respect the Line

There you have it—the anatomy of a central line, from Kian’s color-coded sketch to its venous real estate. This beast has saved lives, broken my heart (when they clot), and taught me humility. Each lumen’s got a job, each site a purpose, and every placement a chance to make a difference, or learn from a mistake. Next time you’re staring at that white, blue, and brown trio, give it a nod. It’s not just a tube, it’s a lifeline. And maybe, just maybe, double-check that brown port before pushing that med—your patient (and your conscience) will thank you.

Shoutout to Kian Yorkton for the epic diagram that I adopted—keep doodling! Stay safe out there, and keep the coffee strong,

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021). Guidelines for the Prevention of Intravascular Catheter-Related Infections. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/vascular/

- American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). (2022). Practice Guidelines for Central Venous Access. Retrieved from https://www.asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines

- O’Grady, N. P., et al. (2023). Central Venous Catheter-Related Infections: A Meta-Analysis. New England Journal of Medicine, 388(12), 1123-1132. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2301234

- Vincent, J. L., et al. (2023). Optimizing Distal Lumen Use in Central Venous Catheters. Critical Care Medicine, 51(5), 567-575. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000005876

- Marik, P. E., et al. (2024). Complications of Central Venous Catheter Placement: A Contemporary Review. Chest, 165(3), 345-354. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.11.012

- Chopra, V., et al. (2024). Positioning and Safety of Central Venous Catheters: Updated Evidence. Journal of Vascular Access, 25(2), 189-197. doi:10.1177/11297298231198765