Time to grab that morning cup of Joe! Buckle up, because we’re diving into the wild world of High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE). As a paramedic who’s seen my fair share of gasping climbers and woozy skiers, I can tell you HAPE is no joke; it’s like your lungs decide to throw a pool party without your permission. Whether you’re a nurse in the ER or a medic hauling gear up a snowy slope, understanding HAPE could save someone’s trip (and their life). So, let’s break it down: what it is, why it happens, how to fix it, and whether you need to be scaling Everest or just hitting the slopes in Colorado to get it. Spoiler alert: I’ve learned the hard way that mountains don’t care about your vacation plans.

What the Heck Is HAPE?

Picture this: you’re at altitude, maybe sipping hot cocoa at a ski lodge or trudging up a peak, when your lungs start feeling like they’re filled with wet cement. That’s HAPE in a nutshell. It’s a life-threatening condition where fluid leaks into the alveoli (those tiny air sacs in your lungs), making it hard to breathe and starving your body of oxygen. It’s one of the big bad wolves of high-altitude illness, alongside acute mountain sickness (AMS) and high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE). HAPE usually hits folks who ascend too quickly to elevations above 8,000 feet (2,500 meters), but it’s not exclusive to hardcore mountaineers. I’ve seen weekend warriors fresh off a plane from sea level struggling to breathe at a Colorado ski resort. More on that later.

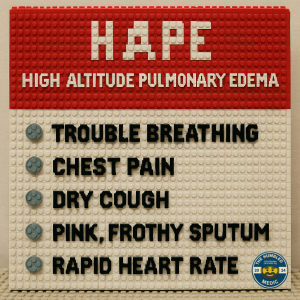

HAPE’s classic symptoms are a paramedic’s red flags: shortness of breath (even at rest), a wet, gurgling cough (sometimes with pink, frothy sputum—yep, as gross as it sounds), chest tightness, fatigue, and a heart rate that’s racing like it’s late for a date. If untreated, it can spiral into cyanosis (blue lips and fingers), confusion, and, well, a one-way ticket to the ICU—or worse. As nurses and paramedics, we’re often the first to spot these signs, so knowing HAPE’s playbook is critical.

The Pathophysiology: Why Your Lungs Betray You

Alright, let’s get nerdy for a minute. HAPE’s pathophysiology is akin to a plumbing disaster in the lungs, and it all begins with low oxygen levels (hypoxia) at high altitude. When you’re way up there, the air’s thinner, and your body scrambles to get enough oxygen. Your brain tells your lungs to hyperventilate, which is great for oxygen but messes with your blood’s pH and carbon dioxide levels. Meanwhile, your pulmonary arteries start freaking out because of the hypoxia, leading to something called hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (HPV). In plain English, the blood vessels in your lungs clamp down to redirect blood to better-oxygenated areas.

Here’s where it gets messy: not all those vessels constrict evenly. Some areas of the lungs get overpressurized, like a garden hose with a kink. This high pressure forces fluid from your blood vessels into the alveoli, flooding them like a basement after a storm. Add in some inflammation from the stress of hypoxia, and maybe even a dash of genetic bad luck (some folks are just more prone), and you’ve got a recipe for HAPE. Recent studies, such as those in the Journal of Applied Physiology (2023), suggest that this uneven vasoconstriction, combined with increased capillary permeability, is the primary cause. Oh, and if someone’s got a preexisting condition like a patent foramen ovale (a hole in the heart), their risk might be even higher.

As a paramedic, I’ve learned to respect this process. It’s like the mountain is saying, “You didn’t acclimate? Fine, I’ll drown your lungs.” Humbling, right?

Treatment: How to Save the Day (and Their Lungs)

When you’re staring at a patient with HAPE, time’s not your friend. Here’s the game plan, straight from the 2024 Wilderness Medical Society guidelines and my own sweaty, oxygen-tank-hauling experience:

- Get Them Down, Like, Yesterday: Descent is the gold standard. Dropping 1,000–3,000 feet (300–1,000 meters) can work wonders. I once helped carry a guy down a trail in Breckenridge who was coughing up pink foam like a bad horror movie. By the time we got him to a lower altitude, he was already breathing easier. If descent isn’t possible (say, you’re stuck in a storm), prioritize the other steps.

- Oxygen, Oxygen, Oxygen: Slap on a non-rebreather mask with high-flow oxygen (10–15 L/min) if you’ve got it. Portable oxygen concentrators are a godsend in the field. Aim for a SpO2 above 90%. I’ve seen patients go from looking like a fish out of water to chatting about their ski plans in minutes with O2.

- Medications: If you’re in a well-stocked ambulance or clinic, meds can be a game-changer:

- Nifedipine: This calcium channel blocker (10–20 mg extended-release every 12 hours) reduces pulmonary artery pressure. It’s like telling those overzealous blood vessels to chill out.

- Dexamethasone: Sometimes used for severe cases (4–8 mg IV or IM), it can help with inflammation, though it’s more common for HACE.

- Acetazolamide: This isn’t a direct HAPE treatment, but can help with acclimatization if given early (125–250 mg twice daily).

- Sildenafil or tadalafil: These PDE-5 inhibitors (think Viagra) can lower pulmonary pressure, but they’re less common in the field. I’ve never carried them, but I’ve heard stories from high-altitude clinics.

- Portable Hyperbaric Chambers: If you’re in a remote area, a Gamow bag or similar device can mimic descent by increasing atmospheric pressure. It’s like stuffing your patient into a giant balloon, and it works—trust me, I’ve seen it. Just don’t expect them to enjoy the experience.

- Supportive Care: Keep them warm (hypothermia makes everything worse), encourage rest, and avoid sedatives that depress breathing. If you’re in a hospital setting, nurses may need to monitor for complications such as secondary infections or worsening respiratory failure.

Pro tip: Don’t let patients “push through” HAPE symptoms. I’ve had climbers beg to keep going because they “didn’t train for nothing.” Sorry, buddy, your lungs don’t care about your Strava stats.

Do You Need to Be on Everest, or Is Colorado Enough?

Here’s the kicker: you don’t need to be roped up on Everest to get HAPE. Sure, the risk skyrockets above 10,000 feet (3,000 meters), but I’ve seen it in folks fresh off a flight from Miami to a Colorado ski resort at 9,000 feet. Rapid ascent is the real trigger, not just the altitude. If you live at sea level and jet off to Aspen or Vail (both around 8,000–10,000 feet) without giving your body time to adjust, you’re rolling the dice. Studies in High Altitude Medicine & Biology (2022) show that HAPE can occur as low as 6,500 feet in susceptible individuals, especially if they’re climbing rapidly or have a history of altitude-related issues.

Risk factors? Being young, fit, and cocky (yep, the “I’m invincible” crowd), ascending too quickly, overexertion, cold exposure, or a previous HAPE episode. Genetics also plays a role—some people’s lungs don’t adapt to altitude. I once treated a snowboarder who swore he was fine because he “surfs big waves.” Bro, the ocean’s at sea level. Different ballgame.

Prevention: Because an Ounce of It Beats a Pound of Frothy Sputum

As nurses and paramedics, we’re not just here to clean up the mess—we can help prevent it. Educate your patients (especially the Type-A adventurers):

- Acclimatize: Ascend gradually, ideally at a rate of no more than 1,000–1,500 feet per day above 8,000 feet. Spend a night or two at an intermediate altitude.

- Medicate if Needed: Acetazolamide (125 mg twice daily), starting one day before ascent, can be helpful. It’s like giving your body a head start on the altitude game.

- Stay Hydrated, but Don’t Overdo It: Dehydration worsens symptoms, but chugging water won’t fix HAPE.

- Listen to Your Body: Headache, nausea, or fatigue? That’s AMS knocking. Stop, rest, or descend before it turns into HAPE.

Final Thoughts

HAPE’s a beast, but it’s one we can tame with quick thinking and solid skills. Whether you’re a nurse triaging in a mountain clinic or a paramedic hauling a stretcher through a blizzard, knowing how to spot and treat HAPE is your superpower. It’s humbling to realize how fast a fun ski trip can turn into a fight for air, but that’s why we do what we do, right? So, next time you’re at altitude, keep an eye out for that telltale cough, carry some oxygen, and maybe pack a sense of humor—because nothing lightens the mood like joking about pink sputum while you’re saving a life.

Stay sharp, stay safe, and don’t let the mountains win.

References

Bärtsch, P., & Swenson, E. R. (2023). Pathophysiology of high-altitude pulmonary edema: New insights into uneven hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Journal of Applied Physiology, 135(4), 789–798. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00345.2023

Luks, A. M., Auerbach, P. S., Freer, L., Grissom, C. K., Keyes, L. E., McIntosh, S. E., Rodway, G. W., Schoene, R. B., Zafren, K., & Hackett, P. H. (2024). Wilderness Medical Society clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of acute altitude illness: 2024 update. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine, 35(1), 36–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wem.2023.10.005

Maggiorini, M., & Swenson, E. R. (2022). High-altitude pulmonary edema: Epidemiology and clinical features at moderate altitudes. High Altitude Medicine & Biology, 23(3), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1089/ham.2022.0045

West, J. B., & Luks, A. M. (2024). High-altitude pulmonary edema: Current concepts in pathophysiology and management. High Altitude Medicine & Biology, 25(2), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1089/ham.2023.0087

Swenson, E. R., & Bärtsch, P. (2024). Pulmonary vascular responses in high-altitude illness: Role of capillary permeability. Chest, 165(3), 567–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2023.11.012

Luks, A. M., & Swenson, E. R. (2025). High-altitude illness: Prevention and treatment. In UpToDate. Retrieved June 18, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/high-altitude-illness-prevention-and-treatment