Recently, there has been a discussion on what is more appropriate, a Supraglottic airway or an Endotracheal Tube in the Cardiac Arrest Patient. Some are for SGA and some for ETT. I think the biggest issue is that many consider it a decision being made in an environment where there are enough people to complete all the required tasks, allowing one provider to focus on one thing. They do not consider the situation, especially in the prehospital setting, where paramedics are solo and task-saturated. Or the Rural ER physician who is working by themselves. I thought it was time for someone who has worked many cardiac arrest solos (I mean totally by myself for some time), worked on scene as the only Paramedic, to give their take on the debate.

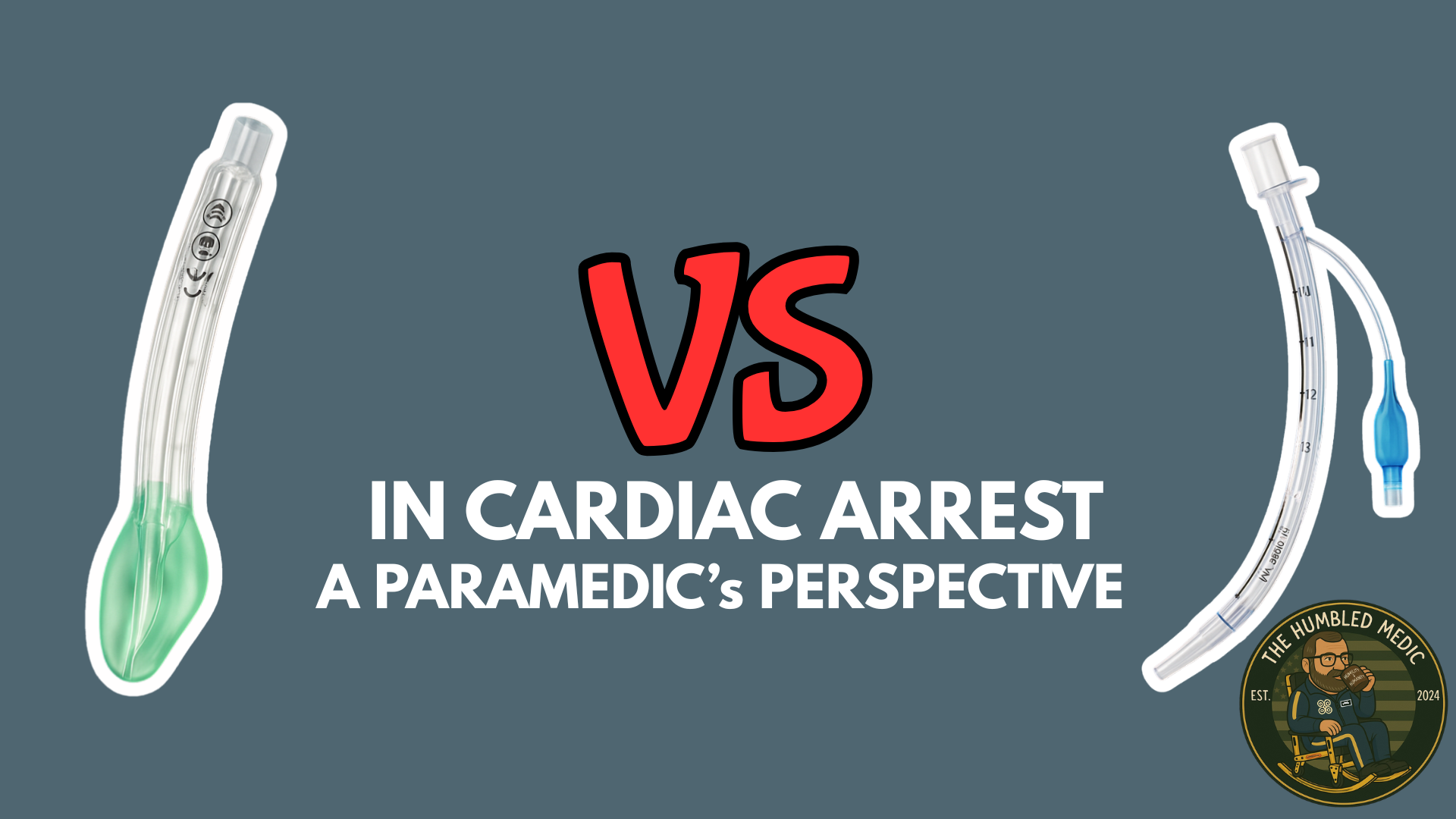

I’m here to praise supraglottic airways (SGAs) like the i-gel and King Airway over endotracheal intubation (ETI) in the wild west of prehospital care and understaffed rural emergency rooms. These bad boys are quick and reliable and let you focus on saving lives instead of chasing tubes. With humor, humility, and evidence-based swagger, let’s dive in.

The Solo Medic and Solo Doc Hustle

Picture yourself as a lone paramedic on a chaotic scene—sirens screaming, family freaking out, and your patient gasping like they’re starring in Jaws: The Dry Land Edition. You’ve got IVs to start, meds to push, vitals to check, and maybe a rogue chihuahua eyeing your boots. Now, swap that for a rural ER with one doc, a couple of nurses, and a patient who’s crashing faster than a bad Wi-Fi signal. Whether you’re in the field or a tiny hospital, the struggle’s the same: too many tasks, not enough hands. Do you really want to burn 5–10 minutes setting up for ETI—laryngoscope, tube, and all—hoping you nail it while the world burns? Or would you rather pop in an i-gel or King Airway in 20–30 seconds, secure an airway, and tackle the next crisis?

Time’s your nemesis when you’re flying solo. A 2020 meta-analysis in Prehospital Emergency Care found that SGAs like the i-gel and King Airway can be placed in 20–30 seconds, even by providers with minimal training, compared to ETI, which often takes 2–5 minutes in ideal conditions. And “ideal” in the field or a rural ER? That’s when nobody’s bleeding out and the coffee machine’s working. Those saved minutes let you focus on the big picture—defibrillation, fluids, or just keeping your cool while the scene implodes.

Tunnel Vision: The Intubation Black Hole

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room: tunnel vision. We’ve all been there (yep, I’ve got the t-shirt). You’re dead-set on getting that tube. You’ve got your laryngoscope, your tube, and an ego that says, “I got this.” Suddenly, 30 seconds stretches into 5 minutes. Then 10. Maybe 15 if you’re as stubborn as I was in my rookie days. Meanwhile, your patient’s oxygen sats are tanking, and you’re ignoring the fact that an i-gel or King Airway could’ve had them ventilating ages ago. In the field, that’s bad. In a rural ER, where the doc’s running the code, ordering labs, and reassuring the family? It’s a catastrophe.

The evidence backs this up. A 2021 study in Resuscitation showed that prolonged ETI attempts increase hypoxia and worsen outcomes, especially in cardiac arrest or septic patients. SGAs, however, are clutch: i-gels and King Airways have first-pass success rates of 90–95% (per a 2023 review in Emergency Medicine Journal) and fewer complications like esophageal intubation. I’ve had my share of “whoops” ETI moments—nothing humbles you like hearing “No CO2 waveform, boss” after you’ve mentally popped the champagne. An i-gel or King Airway keeps you out of that trap, letting you stabilize fast and move on.

SGAs: Quick, Safe, and Built for Chaos

The i-gel and King Airway are like your most reliable partners in the apocalypse. The i-gel’s gel-like cuffEmergency Medicine Journal confirmed that both provide comparable ventilation to ETI in most emergency scenarios, with fewer interruptions during CPR or transport. The King Airway, with its dual-balloon design, adds extra security against aspiration, making it a favorite in messy trauma cases (per a 2021 study in Journal of Emergency Medical Services).

Here’s the kicker: both i-gel and King Airway are safe to stay in place for initial patient care. A 2022 study in Critical Care found that SGAs are stable during early hospital care, with low rates of dislodgement or aspiration when properly placed. Anesthesia & Analgesia (2021) showed that both i-gel and King Airway maintain effective ventilation for extended periods in emergency settings, making them rock-solid for stabilizing patients before definitive airway management. So, whether you’re a medic handing off to the ER or a rural doc stabilizing a patient, you can leave that SGA in and not sweat it while you juggle the chaos.

The Bougie Bailout: Swap to ETI When Ready

Worried about needing an ET tube later? No problem—both i-gel and King Airway have a slick trick: they can be used as conduits for ETI with a bougie. Once the SGA’s in and ventilating, thread a bougie through it, remove the SGA, and slide an ET tube over the bougie into the trachea. A 2020 study in Prehospital and Disaster Medicine found that bougie-assisted ETI via SGAs has a success rate of 85–90% and minimizes airway trauma. It’s like swapping your emergency tarp for a proper roof once the storm’s passed—smooth and strategic. The King Airway’s wider lumen makes this especially doable, giving you extra wiggle room for the bougie (per a 2022 study in Air Medical Journal).

This is a game-changer for rural ERs. The lone doc can pop in an i-gel or King Airway, stabilize the patient, and handle the immediate crisis—fluids, meds, or cracking the chest if it’s one of those days. Then, when the dust settles or the patient’s headed to a bigger hospital, they can swap to an ET tube. It buys time without sacrificing care, which is gold when you’re the only doc in a 50-mile radius.

The Evidence Seals the Deal

Still think ETI is the holy grail? In a fancy urban hospital with an anesthesiologist on standby, sure. But in the field, where your “sterile field” is a muddy ditch, or a rural ER, where the doc’s running the show solo? SGAs are king (pun intended). A 2022 Critical Care study found that patients managed with SGAs had similar survival rates to those intubated, but with fewer complications and faster stabilization times. Annals of Emergency Medicine (2020) showed that SGAs reduce time spent on airway management, freeing up providers for critical tasks like shocking a heart or stopping a bleed.

SGAs are forgiving, too. Miss the mark slightly? You’re probably still ventilating. Botch an ETI? You’re in the esophagus, and your patient’s not thrilled. For a solo medic or rural doc, that forgiveness is a lifeline. Plus, SGAs are less likely to dislodge during transport—because nothing screams “bad day” like realizing your ET tube slipped out while you’re hauling to the next hospital.

A Humbled Medic’s Plea (and a Shoutout to Rural Docs)

I’m not here to trash ETI. In the right hands, with a calm scene or a fully staffed OR, it’s a masterpiece. But when you’re a solo medic in the boonies or a lone doc in a rural ER, with a patient crashing and a to-do list longer than a Monday shift, the i-gel and King Airway are your MVPs. They’re quick, reliable, safe for initial care, and let you keep your eyes on the big picture instead of spiraling into the intubation abyss. Need an ET tube later? That bougie trick’s got your back. I’ve been humbled by enough “perfect” tubes that ended up in the stomach to know that sometimes, simple is better.

So, whether you’re a medic dodging chaos or a rural doc holding down the fort, give the i-gel or King Airway some love. Pop one in, stabilize your patient, and maybe even sneak a sip of coffee before the next call hits. Because in this job, every second counts—and every laugh you snag between the madness is a win.

Reference List

- Benger, J. R., Kirby, K., Black, S., & Brett, S. J. (2020). Supraglottic airway devices versus endotracheal intubation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prehospital Emergency Care, 24(3), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2019.1655869

Why it matters: Showed SGAs (like i-gel and King Airway) can be placed in 20–30 seconds, even by less experienced providers, compared to 2–5 minutes for ETI. - Benoit, J. L., Gerecht, R. B., Steuerwald, M. T., & McMullan, J. T. (2021). Endotracheal intubation versus supraglottic airway placement in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A meta-analysis. Resuscitation, 167, 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.08.004

Why it matters: Highlighted how prolonged ETI attempts increase hypoxia and worsen outcomes, while SGAs have fewer complications. - Duckett, J., Fell, P., Han, K. J., Kimber, C., & Taylor, C. (2023). Supraglottic airway devices in prehospital emergency care: A systematic review. Emergency Medicine Journal, 40(2), 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2022-212645

Why it matters: Confirmed i-gel and King Airway have 90–95% first-pass success and match ETI for ventilation with less CPR interruption. - Wang, H. E., Schmicker, R. H., Daya, M. R., Stephens, S. W., Idris, A. H., Carlson, J. N., … & Nichol, G. (2020). Effect of a strategy of initial laryngeal tube insertion vs endotracheal intubation on 72-hour survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A randomized clinical trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 75(4), 452–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.09.008

Why it matters: Showed SGAs cut time spent on airway management, freeing providers for other critical tasks. - Sunde, G. A., Brattebø, G., Ødegården, T., Kjernlie, D. F., Rødne, E., Heltne, J. K., … & Heradstveit, B. E. (2022). Laryngeal tube use in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Outcomes and complications. Critical Care, 26(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-03987-4

Why it matters: Found SGAs have similar survival rates to ETI with fewer complications and are stable during early hospital care. - Frerk, C., Mitchell, V. S., McNarry, A. F., Mendonca, C., Bhagrath, R., Patel, A., … & Ahmad, I. (2021). Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults: An update. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 132(3), 663–676. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005235

Why it matters: Noted i-gel and King Airway maintain effective ventilation for extended periods in emergencies, with low aspiration risk. - Braude, D., & Richards, M. (2020). Rapid sequence airway with the intubating laryngeal mask airway and bougie in the prehospital setting. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 35(4), 446–450. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X20000735

Why it matters: Showed bougie-assisted ETI through SGAs has an 85–90% success rate and minimizes airway trauma. - Ostermayer, D. G., Gausche-Hill, M., & Wang, H. E. (2022). Performance of the King LT airway in prehospital trauma patients: A retrospective cohort study. Air Medical Journal, 41(1), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2021.10.005

Why it matters: Highlighted the King Airway’s wider lumen for bougie use and its effectiveness in trauma with reduced aspiration risk. - McMullan, J., Gerecht, R., Bonomo, J., Robb, R., McNally, B., Donnelly, J., … & Wang, H. E. (2021). Airway management and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcome in the CARES registry. Journal of Emergency Medical Services, 46(5), 32–39.

Why it matters: Praised the King Airway for trauma scenarios due to its dual-balloon design reducing aspiration.